After Leo's death

his cousin Giulio was the dominant figure in the conclave, but unable to control

the necessary majority, Giulio proposed a compromise candidate, Cardinal Adrian

Florensz, absent in Spain serving as viceroy for Charles V. Cajetan, the famous

Thomist, earnestly seconded this proposal; and almost before they knew it, the

cardinals elected the grave Dutchman.

After Leo's death

his cousin Giulio was the dominant figure in the conclave, but unable to control

the necessary majority, Giulio proposed a compromise candidate, Cardinal Adrian

Florensz, absent in Spain serving as viceroy for Charles V. Cajetan, the famous

Thomist, earnestly seconded this proposal; and almost before they knew it, the

cardinals elected the grave Dutchman.

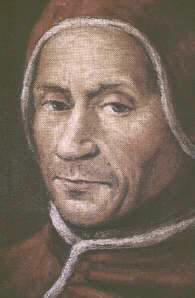

Adrian accepted and chose to be called Adrian VI. Adrian was born in Utrecht, on

March 2, 1459. His parents, poor and pious, gave him a good religious foundation

which was deepened by his early schooling with the Brothers of the Common Life.

Helped financially by Margaret of York, dowager duchess of Burgundy, he took his

doctorate in theology at Louvain in 1491. He taught theology there and published

two books. Among those who came to his lectures was the famous Erasmus.

Chancellor of the university, twice rector, councilor of Duchess Margaret, he

was chosen by Emperor Maximilian to be tutor to his grandson and heir.

Adrian's work with the young prince paid dividends in the sturdy Catholicism of

Emperor Charles V. Sent to Spain on a delicate mission in 1515, he found himself

the next year co-viceroy with the great reformer Ximenes. He was made Bishop of

Tortosa, a cardinal, and grand inquisitor. After Ximenes died, Adrian carried on

as sole viceroy. The election of this Dutchman, this great friend of Charles V,

stunned everyone including the cardinals, but by his firm though tactful

dealings with Charles, Adrian soon showed that he would be no tool in imperial

hands. It was not until late August that Adrian reached Rome, a decidedly

hostile Rome. All the pagan humanists, all the swarm of place-hunters and

job-buyers, feared the stern theologian. And with reason, for Adrian was

determined to reform the Church and to start right in at Rome. Adrian faced a

serious situation. In the East the Turks were about to batter their way into

Rhodes, in Germany Luther's revolt still blazed, and at home the Church needed

reform. Adrian tried to get adequate help for Rhodes, but had to see it fall.

Against Luther he tried to get Erasmus to use his golden pen, but that timid

humanist still hung back. With rare moral courage Adrian, in his instruction to

Chieregati, his nuncio in Germany, fearlessly acknowledged the existence of

abuses, abuses he was determined to stamp out. Adrian devoted himself to this

task. He ruthlessly slashed the expenses of his court. He suppressed useless

offices.

He avoided even the suspicion of favoring his own family. But it takes time to

overcome the resistance of vested interests and the inertia of human weakness.

And time was running out on the sexagenarian Pope. A fierce outbreak of plague

sent the cardinals on the run for a safer climate, and though the indomitable

old Dutchman stayed on and survived, he lost six precious months because little

could be done in the absence of the cardinals; and then when the plague died

down and the cardinals came back, Adrian fell sick. He died September 12, 1523.

The frivolous rejoiced at his passing, but it was a tragedy for the Church.

Excerpted from "Popes

Through the Ages" by Joseph Brusher, S.J.