On

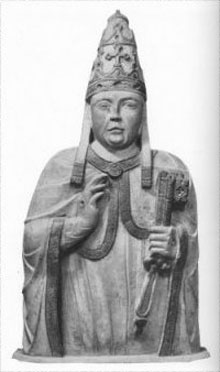

20 December after a conclave which had lasted seven the

cardinals unanimously elected Jacques Fournier, to succeed John

XXII. Athis coronation in the Dominican priory at Avignon on 8

January, 1335 he took the name of Benedict XII.

On

20 December after a conclave which had lasted seven the

cardinals unanimously elected Jacques Fournier, to succeed John

XXII. Athis coronation in the Dominican priory at Avignon on 8

January, 1335 he took the name of Benedict XII.

He was a native of Saverdun in the county of Foix, a

Cistercian monk, a master of the University of Paris a

distinguished theologian who had played a leading part in the

controversy occasioned by John XXII's teaching about the fate of

departed souls. As Bishop first of Pamiers and later of Mirapoix

he had also distinguished himself by the zeal he showed in the

pursuit of heretics.

A true monk, continuing to wear the habit even after his

election as pope, austere in his private as in his public life,

Benedict XII was to show the same zeal in his attempts, never

fully successful, to reform the papal court and the religious

orders and to bring peace to the warring princes of Europe.

From the very beginning of his pontificate Benedict XII

renounced war as an instrument of policy. Neither to defeat the

aggression of the emperor in Italy nor to defend the Papal

States was he prepared to have recourse to arms. With Louis of

Bavaria he at once entered into negotiations which were to

continue to the end of the pontificate, and if no lasting peace

was made between pope and emperor this was due rather to the

opposition and the mistrust of the kings of France and England

than to any lack of good will on the part of the pope. The

attitude of the German princes was intransigent. In 1338 at

Rense they repudiated the claims made by Clement V and John

XXII, declared the Empire totally independent of papal control,

and rejected all the censures by which the two popes had

attempted to vindicate their claims to suzerainty. In this the

princes were supported by the German Church. In Germany the

emperor acted on occasion as though he were possessed of

spiritual as well as temporal authority, annulling the marriage

of Margaret, the heiress of the Tyrol, and providing her and his

son with dispensations from the impediment of affinity so that

they might marry.

Benedict XII worked with some success to prevent the

disastrous conflict between France and England later to be

called the Hundred Years War, which was just beginning, and on

three occasions he was able to bring about a truce or a

temporary cessation of the fighting. But it was the business of

reform within the Church that was the pope's chief concern.

Avignon was notorious for the peculation and the dishonesty

of many of the papal clerks, and for the swarms of benefice

seekers and absentee bishops and clergy who infested the papal

court. Within a month of his election Benedict XII ordered all

diocesan bishops resident at Avignon, and all the clergy having

benefices with care of souls, to return at once to their duties

under pain of deprivation. The abuse of granting abbeys to

non-resident abbots was abolished. In December 1335 the pope

revoked all the favors known as "expectatives", grants of

benefices when they should fall vacant. The mere threat of

inquiry and reform in the different departments of the papal

government, and above all in the office of the pope's marshal,

is said to have brought about a general flight of the guilty

from Avignon. The office of the Penitentiary, which dealt

chiefly with absolution from reserved sins and ecclesiastical

censures and with dispensations, was completely reorganized. A

new staff of secretaries was created to deal with the pope's

secret correspondence, and a new system established of

registering all privileges and favors in order to eliminate

forgeries.

A monk himself and a diocesan bishop for many years before

his election to the papacy, Benedict XII was well aware that

almost all the religious orders at this time were in need of

reform. The Cistercians had long since abandoned much of their

primitive austerity, the rigid observance of poverty and the

excellent system of regular visitation and of general chapters.

The pope renewed these rules, severely limited the abbots'

rights of disposing of monastic property, and ordered all

Cistercian monasteries to maintain students of theology in the

universities.

The most radical reforms were introduced into the Benedictine

order. Thirty-one provinces were established, and each province

was ordered to hold a triennial chapter for the maintenance of

discipline. Other rulings of the pope dealt with the restoration

of the common Iife in the monastery, the care of the property,

and the courses of monastic studies.

Benedict XII was particularly critical of the Franciscans and

imposed on the order a new constitution which was very ill

received and finally abolished by his successor. With the

Dominicans the attempted reform was eves less successful; the

pope was openly resisted by the Master General, and the

controversy was still unsettled when Benedict died on 25 April,

1342.

The pope's reform of the religious orders appears to have

failed because he attempted to do too much too quickly, to make

too many regulations and changes at once and without the men and

the machinery to see that the proposed reforms were put into

practice. All that he did aroused a tremendous antipathy. He was

blamed for his alleged avarice, for being stubborn and

hard-hearted, for his animosity toward the orders of the friars.

Like every reformer Benedict XII made mistakes and he made

enemies; but there can be no doubt of his integrity, of his

personal sanctity, and his ardent desire to purify the Church

and restore the declining prestige of the papacy.

This biographical data is from

"The Popes" edited by Eric John. Published by Hawthorn Books,

Inc of New York.