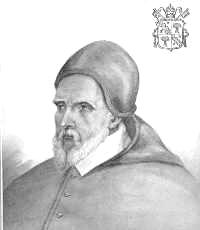

Gregory

XIV, belonged to a noble family of Milan, founded by Conrad, a

German, who, in the time of Otho IV, established himself in

Italy.

Gregory

XIV, belonged to a noble family of Milan, founded by Conrad, a

German, who, in the time of Otho IV, established himself in

Italy.

The mother of Nicolo, Anna Visconti, died, and by the

Caesarean operation Nicolo was brought into the world on the

11th of February, 1535. The infant, though for some time very

weak, gradually gained a little strength. In the course of years

he studied, successively, at Perugia, Padua, and Pavia, at which

last he received the doctorate. While still young, he became a

member of the household of Charles Borromeo. On the 12th of

March, 1560, being then twenty-five years old, he was named

Bishop of Cremona by Pius IV, who sent him to Trent, in which

council he drew up the celebrated decree which prohibited the

plurality of benefices. The Holy See was so satisfied with the

services of Nicolo that without his own consent he was promoted

to the purple by Gregory XIII, on the 12th of December 1583,

under the title of Saint Cecilia.

The sacred electors having entered into conclave, to the

number of fifty-two, on the 8th of October, named as governor of

it Octavius Bandini, who was afterwards a cardinal. there were

several candidates in view for the tiara. Cardinal Montalto

supported Cardinal Scipio Gonzaga, who opposed that design with

a persistency as noble as it was outrageous, and compelled

Montalto to abandon his project.

A great number of votes were united on Cardinal Gabriel

Paleotto, but he had not a sufficient number; two new cardinals

arriving, thirty-six votes were requisite. At length, on the 5th

of December, 1590, at about noon, the fifty-six electors

elected, with open votes, Cardinal Sfondrati, then aged

fifty-five years. He thus on the instant found himself honored

with a charge which he had not expected or desired. At the

moment he was so astonished that, turning to the cardinals, who

saluted him as Holy Father, he said: "God forgive you! What have

you done?"

However, he burst into tears, and refused to walk, and his

voice was choked with sobs. The sedia gestatoria was brought in,

and he was carried in spite of himself into the Basilica of the

Vatican, amidst the acclamations of the populace who wished him

a long reign.

It is known that Gregory XIII gave the purple to Nicolo, and

that he endeavored to refuse it, exclaiming: "Why, there is a

host of prelates more deserving of it than I!" When the

cardinals elected him pontiff they experienced still greater

resistance, but only became the more animated to conquer each

new repulse. Although he would not utter a word, it was

necessary that a name should be selected for him, if he should

persist in not selecting one for himself. That of Gregory was

pronounced, and a feeling of gratitude, evidenced by a slight

smile, was his only reply; but it was taken for a tacit consent.

That slight sign was taken advantage of to prepare for the

ceremony of the coronation of Gregory XIV, which took place on

the 8th of December.

On the 13th of the same month Gregory took possession of

Saint John Lateran.

While he was cardinal, his modesty, his knowledge, and the

purity of his morals endeared him to Saint Philip Neri and Saint

Ignatius Loyola. Gregory deeming it offer the purple to Saint

Philip, the saint declined it, alleging the same reasons that

had formerly been urged by Gregory himself; and, while warmly

thanking him, would not accept that honor. It was related that

when Saint Philip went to pay his respects to Gregory, the

latter rose, hastened to meet him, and said to him: "We are

greater than you in dignity, but you are far greater than we in

sanctity.". He immediately ordered the saint to be seated, an

even to resume his biretta.

To show his respect for the virtues of Ignatius, Gregory, in

1591, confirmed the institute and the constitution of the

Society of Jesus.

We shall here see the famous Arnaud d'Ossat, afterwards

cardinal, figure in a remarkable manner. He will be more

particularly spoken of when honored with the full confidence of

Henry IV of France. At present we confine ourselves to

mentioning his proceedings in the service and name of Queen

Louise of Lorraine, who wished the Roman court to cause solemn

obsequies to be celebrated in honor of Henry III, King of

France, her deceased husband. But that prince had died

excommunicated, and it was difficult to obtain such a compliance

from the court of Rome, which had not deigned to make a reply.

D'Ossat at length obtained a brief, but it could not have been

quite satisfactory to Her Majesty. The pope, after

congratulating Her Majesty upon her having had Masses said, and

having imposed upon herself fasting and almsgiving for the

salvation of souls, proceeded thus: "The ornamentation of a

tomb, the show of mourning, and the funeral pomps, are

consolations for the survivors, not benefits to the dead. For

pious souls who, free from sins, have flown to the Lord, it

matters little that their bodies have a sordid tomb, or none;

even as the costliest tomb does nothing for the impious and

those who are still bound in the bonds of sin."

Following the example of Gregory XIII and Sixtus V, the pope

publicly renewed, by the constitution Romanus Pontifex,

that of Saint Pius V which forbade to alienate or grant in fief

the property of the Roman Church. The whole city of Rome

applauded that just and courageous act. At that precise time

Alphonsus II, Duke of Ferrara, visited Rome, accompanied by a

suite of six hundred gentlemen. Gregory gave him a magnificent

reception, lodged him in the palace, and treated him the same as

he would have treated the most powerful of sovereigns. The

secret object of Alphonsus's journey was to solicit, in favor of

another family than his own, the D'Este family, the reversion of

the duchy of Ferrara. Alphonsus was the last of the house of

Este who had enjoyed that duchy, and before dying he wished to

present that possession to a friendly family, instead of

restoring it to the Holy See, which was the sovereign of the

duchy. Gregory intrusted the examination of that demand to

thirteen cardinals, and, on their report, decided that he could

not grant that favor without infringing the constitution

Romanus Pontifex.

Unfortunately, attacked by a feeling of nepotism, Gregory

named as cardinal his nephew Paulus Emilius Sfondrati, who was

only thirty-one years of age.

By a new constitution Gregory confirmed that given by Pius IV

regarding wagers upon the length of life and the death of the

pontiffs, and upon the creation of cardinals. Some persons

engaged in that illicit and indecent wagering, in order to save

themselves from loss, sometimes disturbed the elections; and

others, to increase their chance of winning, did not blush to

circulate calumnies against worthy men who were thought likely

to be raised to the purple.

He forbade the Capuchins to administer the sacrament of

penance, in order that they might have the more time for the

contemplation of divine things. But Clement VIII, in 1598, again

permitted them to hear the confessions of the faithful.

He published a law upon the immunity of the churches, and

rendered many decrees concerning promotions to bishoprics and

other consistorial dignities.

After consulting the cardinals, the pope issued a bull, at

the solicitation of Cardinal Bonelli, a Dominican, nephew of

Saint Pius V. That bull granted to the cardinals who belonged to

a religious order the right to wear red hats. Till then they had

had to wear hats of the same color as the habit of their order.

On the 9th of June the pope himself, previous to leaving the

Quirinal Palace for the church of the Holy Apostles, to hold a

papal chapel, placed the red hats on the heads of Cardinals

Bonelli and Berner, Dominicans; Boccafuoco, Minor Conventual;

and Petrochini, Hermit of Saint Augustine.

Gregory erected into a religious order the congregation of

the Regular Clerks, Ministers to the Infirm, founded at Rome by

Saint Camillus de Lellis, priest of Buclano, in the diocese of

Chieti. By the constitution Ex Omnibus of the 8th of

March, 1586, Sixtus V had approved the congregation, but

declared that the vows must be spontaneous.

In the castle of Zagarolo, an estate situated twenty miles

from Rome, which belonged first to the house of Colonna, then to

that of Ludovisi, and then to that of Rospigliosi, the final

correction was given to the Bible. That care had been intrusted

to six able theologians, presided over by Cardinal Mark Antony

Colonna.

Few persons had as yet noticed the tendency towards nepotism

from which Gregory had been unable to free himself. That disease

of the pontifical court soon manifested If more fatally. The

pope named his nephew Hercules Sfondrati general of the Holy

Church, and sent him into France at the head of an army of six

thousand Swiss, two thousand Italian infantry, and a thousand

horse. These troops were to assist the French Leaguers, who were

fighting against Henry IV. Subsequently the pope sent into

France, as his nuncio, Marsilius Landriani, who was the bearer

of two monitions. One of those documents concerned all persons

who should espouse the party of Henry, and the other was

especially directed against such nobles as should not abstain

from encouraging heresy.

Spondanus affirms that, besides these monitions, Hercules

Sfondrati was provided with a bull which directly excommunicated

Henry of Navarre.

That was the last effort of this pope's power. He was

suddenly taken ill. He was removed to the palace of Saint Mark,

at Rome, which the republic of Venice had momentarily restored,

and that building was surrounded by gates and guards to prevent

approach. But the condition of the pope was not to be

ameliorated, and he himself considered he was in great danger.

Then he had all the cardinals summoned around him. He

represented that his incapacity for government was still further

increased by his infirmities, and he entreated that, even during

his life, they would elect a successor. That demand was in

opposition to a host of constitutions that had always been

respected. The cardinals at once declared that they would not

consent to be guilty of such an act. Then he exhorted them to

choose, after his death, a successor worthy of the pontificate,

and to choose him promptly, without cabals and without contests.

To the other sufferings of Gregory were added those of the

disease known by the name of the stone. Life was no longer for

him anything but a long torture.

Campana relates that, to relieve the sufferings of the

patient, even pulverized precious stones and gold were

administered to him. Muratori, on that subject, remarks: "This

good pope, then, was surrounded either by stupid physicians or

culpable ministers." The pope soon sank under the violence of

his sufferings, and died on the 15th of October, 1591, at the

age of fifty-six. He had governed ten months and ten days. He

was interred in the Vatican, towards the middle of the Gregorian

Chapel, near Gregory XIII, in a tomb almost destitute of

ornament.

This pontiff, although he yielded to nepotism was

distinguished for his noble virtues. During his short

pontificate he expended considerable sums in favor of the poor.

Some of his ministers did not serve him with that sentiment of

obedience which a minister ought never to forget. During a

scarcity the pope himself was left to see personally to the care

of obtaining a supply of grain. A great number of people in Rome

and the vicinity died, nevertheless, in consequence of that

scarcity. Gregory personally visited the sick, and only

consented to take a little nourishment after he had assisted

those who were on the point of sinking under so much suffering.

All admired his constancy, his piety, his temperance, and a

fund of moral purity, which had made him remarkable from the

period of his being created a bishop. Little inclined to

interfere in foreign politics, he unfortunately listened,

sometimes, too trustingly to Philip II, who was the avowed enemy

of Henry IV of France. The bull which was issued against the

latter prince, who was already prepared to learn and to profess

our holy religion, retarded the success of that difficult

negotiation. Threats were the least likely of all means to

succeed with Henry IV.

This biographical data is from

"The Lives and Times of the Popes" by The Chevalier Artaud De

Montor. Published by The Catholic Publication Society of New

York in ten volumes in 1911.