Hadrian's life is a consolation to those who make a slow start in life. Born

near St. Alban's, England, Nicholas Breakspear started slowly indeed. Educated

at the famous abbey of St. Albans, Nicholas was refused admission as a monk,

probably owing to indolence. After further studies and some drifting in France,

he became abbot of the Monastery of St. Rufus near Avignon. But the community

grew to dislike him so much that for the sake of peace Pope Eugenius removed

him.

Hadrian's life is a consolation to those who make a slow start in life. Born

near St. Alban's, England, Nicholas Breakspear started slowly indeed. Educated

at the famous abbey of St. Albans, Nicholas was refused admission as a monk,

probably owing to indolence. After further studies and some drifting in France,

he became abbot of the Monastery of St. Rufus near Avignon. But the community

grew to dislike him so much that for the sake of peace Pope Eugenius removed

him.

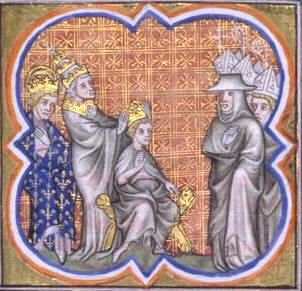

The Pope, however, showed what he thought of Nicholas by making him bishop of

Albano and cardinal. Cardinal Nicholas was sent on a difficult and delicate

mission. Norway and Sweden were becoming restive because their bishops were

under the archbishop of Lund in Denmark. Nicholas handled this affair with great

wisdom and tact. Shortly after he returned from his Scandinavian mission, Pope

Anastasius died and the cardinals elected Nicholas by acclamation. Unwillingly

he accepted. He took the name Hadrian IV. The cardinals chose well. Hadrian was

big. It is pleasant to relate that he showered favors on St. Albans, the

monastery which rejected him, and St. Rufus, the monastery which had driven him

out. Hadrian is noteworthy as the only English pope --and also because he gave

Ireland to King Henry II of England. He allowed Arnold of Brescia, that stormy

petrel of Roman politics, to be executed. He fought the Normans and was beaten

by them at Benevento in 1156. But overshadowing all other events of his reign

was the start of the papacy Hohenstaufen fight. Frederick of Hohenstaufen, the

emperor, was filled with absolutist ideas. At first, indeed, he helped Hadrian,

but a clash between an emperor consumed with power lust, and a pope determined

to be independent was inevitable.

At the diet of Besancon the growing strain snapped the cable of understanding

with a crash that reverberated around Europe. The Pope had sent legates with a

letter reproving the Emperor because he had allowed the murder of the archbishop

of Lund by a robber baron to go unpunished. In the letter Hadrian appealed to

the Emperor's gratitude because of the benefits he had given him. The Germans

took this to mean that the Pope claimed to have given Frederick the empire as a

fief! Frederick sent the delegates packing, and although Hadrian explained that

by the word "beneficia" he meant not fiefs but benefits, real peace did not

come. In 1158 Frederick captured Milan, and with the Lombard cities overawed,

proceeded to hold the famous diet of Roncaglia. There he played the absolutist,

and practically destroyed the self-rule of the Lombard cities. Hadrian demanded

that he recognize the Pope's independence in Rome. Frederick's answer was to

stir up the Romans to drive Hadrian out of the city. Hadrian threw his support

to the embattled communes of Lombardy. In the midst of this strife Hadrian died

at Anagni, September 11, 1159.

Excerpted from "Popes

Through the Ages" by Joseph Brusher, S.J.