There are a few

characters in whom the Renaissance spirit and the Christian spirit met in so

harmonious a blending that in them the best spirit of the age seemed incarnate.

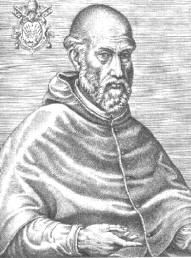

St. Thomas More was one such. Pope Marcellus II was another.

There are a few

characters in whom the Renaissance spirit and the Christian spirit met in so

harmonious a blending that in them the best spirit of the age seemed incarnate.

St. Thomas More was one such. Pope Marcellus II was another.

Marcello Cervini was born May 6, 1501, of a noble family of Montepulciano. His

father Ricciardo, a scientist, started Marcello on the path to knowledge.

Marcello was a serious young man, yet so agreeable that he was liked everywhere.

At Siena, where he continued his education, he was so respected that his

presence was enough to cut off evil conversation. He completed his education at

Rome, where he made such an impression on Clement VII that the Pope ordered

Marcello to collaborate with his father on a book dealing with calendar reform.

He helped his father not only on the book but on his estates. Marcello proved to

be a practical farmer as well as a scholar, a conjunction not always found.

After his parents' death he settled the family, then went to Rome where he

served first in the papal chancery, then in the diplomatic corps. Cardinal

Farnese, who had studied under Marcello and liked him, used him a great deal in

affairs of state. His advancement was swift.

Bishop of Nicastro and administrator of Reggio and later of Gubbio, he took

great pains to reform those dioceses. Created cardinal in 1539, he served as

legate at Trent, where he did valuable work on the decrees on scripture,

tradition, and justification. Marcello is remembered by scholars as one of the

great directors of the Vatican Library. By his cataloguing, his acquisition of

new manuscripts and his printing of old ones he contributed a great deal to

scholarship. He was a friend to young writers and such scholars as Seripando,

Sirleto, and Panvinio owed much to him. Such then was the man the cardinals

chose to succeed Julius III. His election on April 10, 1555, was hailed with

joy, especially by those eager for reform. Marcellus II (he retained his own

name) wasted no time. He cut down the display of the coronation. He rigidly

refused to favor his relatives. He issued severe regulations for his household.

He proclaimed his intention of resuming the Council of Trent. Men felt a golden

age of the papacy was dawning; but the greater the hope, the greater the

disappointment. The long ceremonies of the coronation and Holy Week had so

exhausted the delicate Pope that he fell into a fever. In spite of doctors'

orders he continued to work. Although the fever persisted, the doctors were not

alarmed; but on May I, 1555, after a pontificate of only twenty-two days, Pope

Marcellus died in his sleep. His memory is enshrined in Palestrina's great Mass

of Pope Marcellus, and still more in the hearts of those who reverence goodness

and scholarship.

Excerpted from "Popes

Through the Ages" by Joseph Brusher, S.J.